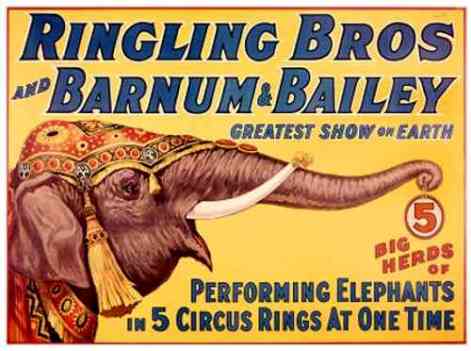

“Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus took a final, bittersweet bow” last year, staging its last three shows “after 146 years of entertaining American audiences with gravity-defying trapeze stunts, comically clumsy clowns and trained tigers…many spectators said they came precisely because it was the last chance to witness a spectacle that once felt as if it might be around forever — until changing times and mores proved more powerful.”

There’s general agreement that the death knell was the departure of the elephants, the biggest draw on earth for the greatest show on earth. And yes, I know. You shouldn’t treat animals, magnificent – or lowly – as a spectacle for humans. Of course, that would mean closing every zoo in America, with their artificial ‘scapes and cages and putting animals through unnatural paces. And maybe they should be closed, although of course at the rate we’re going decimating the natural habitats of this planet there won’t be any of them left in a generation or two.

But this note about RBB&BC, filed away without posting last year, came back go mind this morning when I saw a story on CBS Sunday Morning about holographic concerts. Basically, they’re reviving dead musicians the same way they create CGI animations that use an actual actor to do the movement and superimpose a computer-generated head, then merge it with a voice recording. They have a hologram of Maria Callas “touring” with a live orchestra, and Rob Orbison with a live backup band. The problem isn’t that these people are dead, it’s that real and not real are getting irremediably muddied. People are apparently paying real money to attend concerts of an immensely popular animé “pop star.” It gets worse. There was something about the Indian Prime Minister having won a sweeping electoral victory following an intensive campaign of holographic speeches around the country.

We’re losing something and I’m not sure we can get it back. Because if you don’t have a point of comparison, you accept what is as the way things are supposed to be. We sit in front of computers all day, electronically socializing. We watch endlessly appalling stories of deviant human behavior on whatever news channel best fits our preconceived political notions. We are inured to violence because we can’t bear to keep letting it affect us and have reached the spectacularly frightening point where 11 school shootings in 26 days is some kind of sick norm. There’s no buildup, no time to digest or take our breath, just an endless assault on our sensibilities and humanity.

I saw a clip of Walter Cronkite this morning, and remembered the shared experience of everyone in the country getting their evening news from a respected and unassailably credible source. Of shared movies and television shows, however inane, but limited enough in variety that lots of people had the same experiences. Of time with friends and family uninterrupted by the ridiculous urgency of Twitter and Facebook. The aggregate effect, at least in recollection, was a sense of things being calm and under control, even when they weren’t (think Cuban missile crisis or the multiple assassinations of the 1960s or even Watergate). That someone is in control, that there’s a steady hand at the wheel, and that tomorrow is more than likely going to be okay. And predictable.

But now the circus, that most predictable of childhood memories and dreams, is gone too. Oh, there’s Cirque du Soleil, but it’s not the same thing. We’re losing not just the way we’d perhaps like things to be, but the continuity of human experience.

“David Eisenberg, a business development manager from Massapequa, N.Y… first beheld the circus half a century ago with his grandfather. He took his daughter when she was little, and he and Rachel, now 25, returned one more time Sunday night.”

The problem isn’t just the business one, that the elephants – the big draw that brought people out because they appealed to our inner child – are gone, and without them the rest of the acts are just not stimulating enough to get us to the big top. In marketing, they describe the modern response to this as disruption, a change in the value curve such that some features become more important and others less so, to create a stimulating new proposition for a new generation: think Cirque du Soleil. But the problem is deeper, more visceral.

We’re all overstimulated. I watched a young grandmother a few months ago with a toddler. As the little girl played with a soap bubble wand at a beautiful spot by the bay, her nana was – you guessed it – interacting with the world on her smart phone. Not that she was ignoring the little girl; there were certainly attentive if intermittent words of encouragement and pleasure. But it’s indicative of an electronic bombardment that we’re naturally wired to buy into that’s ultimately self-centered, and that, hopelessly, never stops anymore.

By contrast, consider the circus. The one of childhood memories. There was the buildup, the anticipation, of an annual event. There was the magic of astonishing and death-defying feats. There was the awesome if politically incorrect wonder of the big animals. The makeup and costumes. The smell of popcorn and cotton candy. What does that all mean today? Not much, when we don’t have to wait for or anticipate anything. It’s right there in our pocket, on our phone. Want to watch the circus? Go to YouTube and view all of its splendor on a 4×6 inch screen. Move on when you’re bored.

Things die because there’s not enough demand for them to overcome the opportunity cost of deploying investments elsewhere. The parent company of the now-defunct RBB&B simply couldn’t make (enough) profit doing the Greatest Show on Earth. Especially once they got forced by modern sensibilities to retire the elephants. But that was symptom and not cause.

The cause is that our instant-on-all-the-time-world has diminished room for anticipation. It has no accommodation for attention span or the wonder of a single and singular event. It has little appetite for nostalgia. Worst of all, for those of us on the tail end of the product life cycle, it has no time for elephants.

Because, it occurs to me, we’re the elephants and no one seems to be much interested in our wisdom, power, and ability to entertain. At least not enough to make room for us in the big top of 2018.